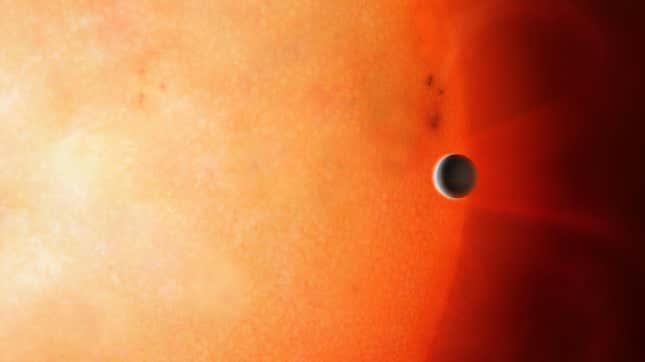

An international team of astronomers is reporting the discovery of a Neptune-like planet located some 920 light-years from Earth. Dubbed the “Forbidden Planet” by the researchers, this celestial object is locked in a freakishly close orbit with it host star in a configuration rarely seen.

New research published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society describes the discovery of a Neptune-like planet that’s so close to its host star that a single orbit takes just 1.34 days. A Neptune-like planet has never been found so close to its host star. And in fact, astronomers came up with a term, the “Neptune desert,” to describe this up-close-and-personal stellar zone. Unlike small and durable rocky planets or massive Hot Jupiters, Neptune-like planets aren’t supposed to exist at such a close distance, as the host star would burn the intermediate-sized object down its core. But this new exoplanet is defying those expectations.

More formally, the exoplanet has been given the designation NGTS-4b. It was discovered by the Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS)—a ground-based telescope at the European Southern Observatory’s Paranal Observatory in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

A team led by University of Warwick astronomer Richard West used the tried-and-true transit method to detect and characterize the distant orb. This exoplanet, which is roughly 20 percent smaller than Neptune and roughly three times the size of Earth, was spotted as it moved between us and its host star, resulting in a brief but periodic dimming of the starlight. Incredibly, they measured that the star dimmed by less than 0.2 percent—something no ground-based telescope has ever done before, according to a press release issued by the University of Warwick.

But that’s not the only pioneering accomplishment of NGTS. The Forbidden Planet’s achingly brief orbital period of 1.34 days is the shortest to ever be detected by a ground-based telescope. It’s also the smallest exoplanet ever to be discovered from the ground. Not bad for a single discovery.

Not to mention the whole “Neptune desert” thing.

“The term ‘Neptune desert’ came from observing that there were few intermediate-mass planets at very short [orbital] periods,” Coel Hellier, an astronomer at Keele University who didn’t contribute to the new study, explained to Gizmodo in an email.

Previously, astronomers had discovered Neptune-sized planets with orbital periods as short as 5.44 days (WASP-166b) and 4.23 days (HAT-P-26b). As for orbital periods between one to four days—the short-period Neptunian desert—not so much.

The ascribed reason, explained Hellier, is that intermediate planets (i.e. large, low-density ‘Neptune’-mass planets) are boiled away by radiation pouring out of their star. Larger, Jupiter-mass planets are able to survive because their greater mass and gravity enables them to keep hold of their atmosphere, while smaller, rocky planets are much denser, and so less susceptible to being boiled away, said Hellier.

As for the name “Forbidden Planet,” Hellier said the discovery of this exoplanet clearly disqualifies its “forbidden” or impossible status, as it obviously exists. The most likely explanation for NGTS-4b, he said, is that it recently arrived to its current location, and its atmosphere hasn’t had enough time to boil away.

“This planet doesn’t have enough mass to hold onto its atmosphere, given the fierce heat from being so close to its star,” Hellier told Gizmodo. “That means that it was likely born much further out from its star, and has moved to its current short-period orbit only recently. All credit to the NGTS team for finding a planet unlike those found previously by transit surveys.”

Indeed, this exoplanet may be a very good example of the planetary migration hypothesis at work. NGTS-4b likely formed in the outer reaches of this planetary system, but it crept closer to its host star, eventually finding itself in its current, perilous orbital position. The authors of the new study said this is a distinct possibility, but they offered a second scenario: NGTS-4b was unusually massive.

Astronomer Hannah Wakeford from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, not involved with the new study, said this planet was probably once much larger than it is now, and its proximity to the star is causing its atmosphere to be blown from the planet. Consequently, NGTS-4b is getting smaller and denser over time as the mass becomes dominated by the core mass and not the atmospheric mass.

“The way to test if this is the case is to look at the planetary transit in the ultraviolet [spectrum] searching for signatures of escaping hydrogen from the atmosphere,” said Wakeford in an email to Gizmodo. “This would then show that this planet is like many of the other... exoplanets found in the Neptune desert, and suggests that over time the mass will drop such that it becomes a part of the population of planets below the desert cut-off which have lost all of their atmosphere.”

Looking ahead, West and his colleagues are planning to scour their data to see if any similar objects can be found in the Neptune desert. Perhaps “the desert is greener than was once thought,” he said in the Warwick release.