How Snapchat dysmorphia drives teens to plastic surgery to copy looks phone camera filters give them

- Young people look obsessively through heavily filtered photos of influencers on Instagram, Snapchat and Weibo, and of themselves, then ask surgeons to copy them

- More than half the plastic surgery clients in China are under 28; the average age at which western Europeans have cosmetic surgery has fallen by five years

A decade ago, clients came into plastic surgery clinics carrying photographs of models, celebrities or even a particularly attractive family member. Today, they clutch heavily filtered images of themselves.

“Social media is having a substantial effect on our culture as a whole,” says Julian De Silva, a plastic surgeon based in London’s Harley Street. “It’s heavily influencing plastic surgery trends and cosmetic treatments – and there has been a very rapid change over the last five years.

“Patients are taking more photos of themselves than ever, and as a result they are far more self-conscious about their appearance. Flaws they would previously have ignored have, since the advent of social media, plagued them.”

As a result, not only are the number of plastic surgery cases on the rise globally, the average age of clients has dropped, falling from 42 to 37 in western Europe.

In China, the statistics are particularly stark. A report released last year by cosmetic procedure platform GengMei (which means “more beautiful” in Chinese) valued the domestic cosmetic surgery industry at US$71.8 billion. The report found that the number of new clinics opening last year increased by 10 per cent in comparison with 2017.

It also found that 22 million Chinese underwent cosmetic procedures in 2018, and that consumers under the age of 28 accounted for a whopping 54 per cent of the total client base.

Many Chinese people travel to the South Korean capital, Seoul, for plastic surgery. There, sleek clinics can be found on many street corners, promising women the face and body of a teenage television star. Double-eyelid surgery has become so normal that girls receive it as an 18th birthday present and, as a result, a third of all South Korean women have gone under the knife. How much of this activity is the result of social media?

“I work predominantly with teenagers and there is definitely a narrowing of what it means to be beautiful, not just for girls but also for boys,” says Jamie Chiu, a Hong Kong-based psychotherapist specialising in body dysmorphia.

“There is no doubt that it does hurt your self-esteem to grow up in this social-media-obsessed environment, with a culture that tells you that to be noticed you need to be beautiful – and that being beautiful means looking like an Instagram model.”

A report by Chiu shows that, after looking at social media, nearly half of all teenagers feel unhappy, or even have feelings of depression, when they think about their own bodies. Whether they are looking at Snapchat, Weibo or Little Red Book, the impact is the same. Whereas in the past vulnerable young people were comparing themselves to models and actors – people whose lives are aspirational and detached from their reality – today they are comparing themselves to an influencer of a similar age who lives in a similar town.

“Influencer culture has a far bigger impact on mental health than any glossy magazine of the past would have,” Chiu says. “You get a different sense of reality when your idols are just like you but half your size and in designer clothes.”

Then there is the very modern, meta phenomenon of feeling you are inferior to your own filtered self.

While most smartphones offer the ability to make spots vanish and enhance skin, the heavy filters on platforms such as Snapchat and Meitu can Disney-fy your entire face and body, making your eyes bigger and your lips fuller; the gap between the reflection in the mirror and the image on the phone is becoming a chasm.

The term Snapchat dysmorphia gained traction when a 2018 report published by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery explained that more than half of all facial plastic surgeons have patients who have requested procedures to make them look better on social media – an increase of 13 per cent from a year earlier – with many asking to look more like the way they appear when using a Snapchat or Meitu filter.

“I think it’s causing real problems,” says Chiu. “Filters in particular are leading to a dangerous trend where people feel insecure about not being as beautiful as their own filtered selves. I have a client who tells me all the photos she saves are edited and heavily filtered. Then she scrolls through these photos and thinks how much better she looked last month than now – even though in reality, she never looked like that, her brain just got tricked.”

Filters are also creating unrealistic expectations of what plastic surgery can achieve.

There is definitely a narrowing of what it means to be beautiful, not just for girls but also for boys

“Some patients will come with a photograph of an edited version of themselves and ask to look like that, but so much of what they want, such as moving the position of the eyes, is impossible anywhere but on an app,” says De Silva.

“This also feeds into the current subculture where people want extremes of appearance, so lips that look very voluptuous – but I always say no, because I don’t want them to look out of sync with normality.”

Social media’s role does not end there. Hugely successful apps bring together young women who are interested in surgery, creating a virtual community around physical insecurity.

So-Young – a marketplace in app form for cosmetic procedures in China – is the most famous globally, and generated US$80 million in business last year. It offers information on 5,000 clinics and hospitals, and almost 10,000 doctors, and allows clients to pay through its app, and post their photos online afterwards.

“I’m wary about all this,” says De Silva, “There is no level of scrutiny or protection on what is put out there. Anyone can say anything and there still aren’t enough checks and balances in place.

“Fillers around the eyes, for example, don’t require a doctor or even nurse’s certificate, but going to an untrained health provider who makes a mistake can lead to lifelong complications with vision.”

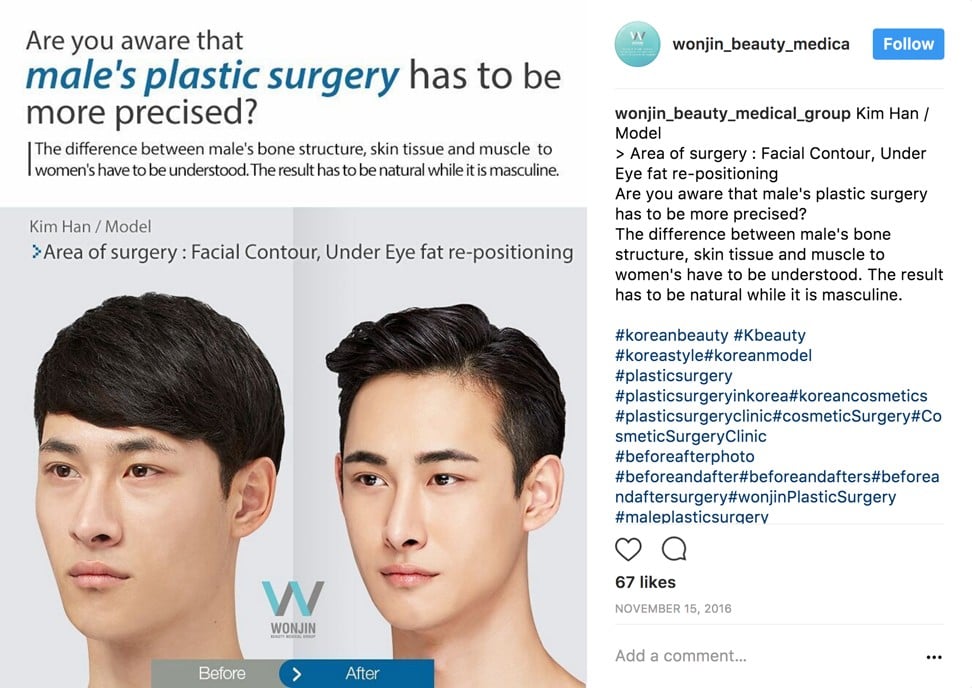

Another impact from social media is its glorification of the entire cosmetic surgery process. On Instagram, #plasticsurgery has 2.5 million posts, with a number of celebrities and influencers sharing before-and-after shots.

In 2017, K-pop girl group Six Bomb released a single called Becoming Prettier, an uninhibited celebration of plastic surgery, specifically the US$90,000 makeover the band members underwent. It got hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube.

As a result, much of the stigma around plastic surgery has been lifted, and the globalisation of culture – which in many ways is led by social media – has changed traditional concepts of beauty.

“Our perception of beauty changes every decade,” says De Silva. “The feeling now is the most attractive quality is a blend of ethnicities. We did research on different aspects of the face and the ‘golden ratio’ of the modern era is very multicultural.”

As with all major changes in culture, it is rarely wholly good or bad. When vulnerable young people are involved, however, we need to ensure they aren’t being exploited by a world they haven’t been fully exposed to yet.

“I don’t want to pass judgment on plastic surgery. In my opinion, it’s neither good nor bad – it’s the reasons why people have it that I’m interested in,” says Chiu. “If you’re doing it because there is one physical flaw that bothers you, then go ahead. But if it’s because you fundamentally don’t like yourself, then one operation won’t change anything.”

As we move deeper into the tech era, it is often easier to like our perfectly curated online selves more than our messier real-life personae. As in any fairy tale, however, allowing too much fantasy to seep into real life all too often ends in tears.